Building a Database of CSAM for AOL, One Image at a Time

If you work in content moderation or with a team that specializes in content moderation, then you know that the fight against child sexual abuse material (CSAM) is a challenging one. The New York Times reported that in 2018, technology companies reported a record 45 million online photos and videos of child sexual abuse. Ralph Spencer, our guest for this episode, has been working to make online spaces safer and combatting CSAM for more than 20 years, including as a technical investigator at AOL.

If you work in content moderation or with a team that specializes in content moderation, then you know that the fight against child sexual abuse material (CSAM) is a challenging one. The New York Times reported that in 2018, technology companies reported a record 45 million online photos and videos of child sexual abuse. Ralph Spencer, our guest for this episode, has been working to make online spaces safer and combatting CSAM for more than 20 years, including as a technical investigator at AOL.

Ralph describes how when he first started at AOL, in the mid-’90s, the work of finding and reviewing CSAM was largely manual. His team depended on community reports and all of the content was manually reviewed. Eventually, this manual review led to the creation of AOL’s Image Detection Filtering Process (IDFP), which reduced the need to manually review the actual content of CSAM. Working with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), law enforcement, and a coalition of other companies, Ralph shares how he saw his own team’s work evolve, what he considered his own metrics of success when it comes to this work, and the challenges that he sees for today’s platforms.

The tools, vocabulary, and affordances for professionals working to make the internet safer have all improved greatly, but in this episode, Patrick and Ralph discuss the areas that need continued improvement. They discuss Section 230 and what considerations should be made if it were to be amended. Ralph explains that when he worked at AOL, the service surpassed six million users. As of last year, Facebook had 2.8 billion monthly active users. With a user base that large and a monopoly on how many people communicate, what will the future hold for how children, workers, and others that use them are kept safe on such platforms?

Ralph and Patrick also discuss:

- Ralph’s history fighting CSAM at AOL, both manually and with detection tools

- Apple’s announcement to scan iCloud photos for NCMEC database matches

- How Ralph and other professionals dealing with CSAM protect their own health and well-being

- Why Facebook is calling for new or revised internet laws to govern its own platform

Our Podcast is Made Possible By…

If you enjoy our show, please know that it’s only possible with the generous support of our sponsor: Vanilla, a one-stop shop for online community.

Big Quotes

How Ralph fell into trust and safety work (20:23): “[Living in the same apartment building as a little girl who was abused] was a motivational factor [in doing trust and safety work]. I felt it was a situation where, while I did basically all I could in that situation, I [also] didn’t do enough. When this [job] came along … I saw it as an opportunity. If I couldn’t make the situation that I was dealing with in real life correct, then maybe I can do something to make a situation for one of these kids in these [CSAM] pictures a little bit better.” –Ralph Spencer

Coping with having to routinely view CSAM (21:07): “I developed a way of dealing with [having to view CSAM]. I’d leave work and try not to think about it. When we were still doing this as a team … everybody at AOL generally got 45 minutes to an hour for lunch. We’d take two-hour lunches, go out, walk around. We did team days before people really started doing them. We went downtown in DC one day and went to the art gallery. The logic for that was like, you see ugly stuff every day, let’s go look at some stuff that has cultural value or has some beauty to it, and we’ll stop and have lunch at a nice restaurant.” –Ralph Spencer

How organizations work with NCMEC and law enforcement to report CSAM (28:32): “[When our filtering tech] catches something that it sees in the [CSAM] database, it packages a report which includes the image, the email that the image was attached to, and a very small amount of identifying information. The report is then automatically sent to [the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children]. NCMEC looks at it, decides if it’s something that they can run with, and if it is … they send the report to law enforcement in [the correct] jurisdiction.” –Ralph Spencer

When “Ralph caught a fed” (37:37): “We caught the guy who was running the Miami office of [Immigration and Customs Enforcement]. He was sending [CSAM]. … That one set me back a little bit. … I remember asking the guy who started the team that I was on, who went on to become an expert witness. He worked in the legal department, and his job basically was to go around the country and testify at all the trials explaining how the technology that caught these images worked. I said, ‘I got an email about this guy from ICE down in Florida, was that us?’ He’s like, ‘Yes, that was you.'” –Ralph Spencer

Facebook’s multiple lines of communication offer multiple avenues for content violations (45:08): “Zuckerberg is running around talking about how he’s trying to get the world closer together by communicating and increasing the lines of communication. A lot of these lines just lead to destructive ends.” –Ralph Spencer

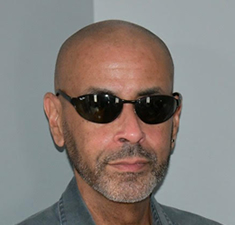

About Ralph Spencer

Ralph Spencer has been working to make online spaces safer for more than 20 years, starting with his time as a club editorial specialist (message board editor) at Prodigy and then graduating to America Online. He’s wrestled with some of the most challenging material on the internet.

During his time at AOL, Ralph was a terms of service representative, a graphic analyst, and a case investigator before landing his final position as a technical investigator. In that position, he was in charge of dealing with all issues involving child sexual abuse material (CSAM), then referred to as “illegal images” by the company. Ralph oversaw the daily operation of the automated processes used to scan AOL member email for these images and the reporting of these incidents to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) which, ultimately, sent these reports to the appropriate law enforcement agencies.

The evidence that Ralph, and the team he worked with in AOL’s legal department, compiled contributed to numerous arrests and convictions of individuals for the possession and distribution of CSAM. He currently lives in the Washington, DC area and works as a freelance trust and safety consultant.

Related Links

- Sponsor: Vanilla, a one-stop-shop for online community

- Ralph Spencer on LinkedIn

- National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC)

- Andrew Vachss

- Apple’s extended protections for children

- Derek Powazek on Community Signal

- Derek’s thread regarding Apple’s announcement

- The Internet Is Overrun With Images of Child Sexual Abuse. What Went Wrong? (the New York Times)

- The Facebook Files (the Wall Street Journal)

- Jeff Horwitz on Community Signal

- Sophie Zhang on Community Signal

- The Facebook Whistleblower, Frances Haugen, Says She Wants to Fix the Company, Not Harm It (the Wall Street Journal)

- Facebook’s Zuckerberg defends encryption, despite child safety concerns (Reuters)

- aol.com by Kara Swisher

Transcript

[music]

[00:00:04] Announcer: You’re listening to Community Signal, the podcast for online community professionals. Sponsored by Vanilla, a one-stop-shop for online community. Tweet with @communitysignal as you listen. Here’s your host, Patrick O’Keefe.

[00:00:25] Patrick O’Keefe: Hello and thank you for listening to Community Signal.

Before we get started, I want to give a warning that we’re going to talk quite a bit about child sexual abuse material, or CSAM, which are photos and videos containing sexually explicit activities involving children. You may have heard this referred to as child pornography or kiddie porn, but there is an effort to stop using those labels as pornography often refers to a consenting activity between adults. Instead, child sexual abuse material says what it is in the name; sexual abuse of children. These terms pop up a couple of times in this episode talking with a true veteran of this work, but in general, I try to use CSAM as my default terminology and encourage you to do the same. This is a sensitive subject and we’ll be talking with Ralph Spencer who has deep first-hand experience in tackling this horrific problem online.

Thank you to our Patreon supporters who back our show giving us the encouragement to tackle the topics that matter. This includes Carol Benovic-Bradley, Paul Bradley, no relation, I don’t think, and Rachel Medanic. If you’d like to join them, visit communitysignal.com/innercircle.

Before we called it trust and safety, Ralph Spencer was doing the work. For more than 20 years, starting with his time as a club editorial specialist or message board editor at Prodigy, and then graduating to America Online, he’s wrestled with some of the most challenging material on the internet. During his time at AOL, Ralph was a terms of service representative, a graphic analyst, and a case investigator before landing his final position as a technical investigator. In that position, he was in charge of dealing with all issues involving child sexual abuse material, then referred to as illegal images by the company.

Ralph oversaw the daily operation of the automated processes used to scan AOL’s member email for these images and reporting incidents as to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children or NCMEC, which ultimately sent these reports to the appropriate law enforcement agencies. The evidence that Ralph and the team he worked with in AOL’s legal department compiled contributed to numerous arrests and convictions of individuals for the possession and distribution of child sexual abuse material. He currently lives in the Washington DC metro area and works as a freelance trust and safety consultant. Ralph, welcome to the show.

[00:02:34] Ralph Spencer: Thank you. Thank you, Patrick. Thank you for having me.

[00:02:37] Patrick O’Keefe: It’s a pleasure to have you. You were at AOL for almost 20 years, which led you to the role of technical investigator. What is a technical investigator?

[00:02:45] Ralph Spencer: That depends. It encompasses a whole lot of stuff. What we did was of the range of criminal investigation. When I actually got the position as technical investigator, we did what’s called legal compliance. In other words, anything that law enforcement may have considered an illegal activity that was done using an AOL account, law enforcement would send us a request for information about the account. They would send subpoenas, they would send search warrants, they would send preservation letters.

Basically, the information that they wanted to get with that documentation was they were looking for the actual real identity, the name and address of the account holder, they could request his IP log, his or her IP logs, billing information, including credit card information, and emails. One thing they always tried to get but we never kept it was the IM logs, the instant messenger that AOL sunsetted a couple of years back. They wanted all of that but we never kept all of that. We gave the member the option to log the IM messages that he placed with whoever he placed them with, but that was kept on his computer. If the person managed to do that, all they had to do was serve the person, him or her, with a search warrant, and if the person had the IM logs on there, they could get them then.

That’s basically about what the technical investigation dealt with. It also dealt with actual investigation. There were issues we’d get in stuff like school bomb threats or death threats against public figures, or basically just death threats against people who were concerned, that kind of thing. We would investigate those. If it was done using an AOL account, we could generally, most of the time, find out some information about that. We were doing stuff like that.

There’s also a realm that I never dealt with but there’s one of my co-workers who’s still there. They do pin registers and stuff like that to government issues, warrants for that kind of stuff. We do that kind of stuff also. That’s it in a nutshell.

[00:04:46] Patrick O’Keefe: When you describe that, you talk a lot about sort of reactive things, but you were also actively detecting issues as well, right?

[00:04:53] Ralph Spencer: That’s right. Basically, it’s now called like you said, child sexual exploitation, child sexual abuse material. Back when I was dealing with it, we just basically called it what it was, which is child pornography, but everybody wants to use the other term now, so I have to defer to that.

[00:05:08] Patrick O’Keefe: That makes a lot of sense. You told me before the show that you just fell into this work. Prior to AOL, you have worked that Prodigy, starting in ’92 as a senior club editing specialist. How did you end up on this career path?

[00:05:19] Ralph Spencer: I got laid off from Prodigy and going around looking for another job, ended up moving back down to the DC area. I was working for the DC government in the Office of Personnel and I was making half the money I was making at Prodigy and had basically twice the amount of bills and whatnot. I just got mad one day and sent three cover letters and three resumes out. I sent one to Bell Atlantic because they hadn’t decided to declare themselves Verizon at that time. Word on the street was that they were looking to start an online service, so I thought I’d try to jump in on that early.

Then I sent one to ABC TV over here off of Connecticut Avenue for what they call vacation relief. I was a studio technician for what used to be the Financial News Network up in Manhattan before they got bought out by CNBC. I ran camera, chyron, and that kind of stuff. Then the last one was to a up-and-coming company in Vienna, Virginia, used to be called Quantum Computers. Now, at that time was called America Online. They were the only ones that answered back. That’s basically how I ended up with AOL.

Basically, the experience I had at Prodigy was pretty much tailor-made for getting that job. I worked as what they termed a terms of service representative, which basically meant that any complaints that came in about stuff that happened in the chat rooms, email complaints, somebody threatened me or somebody said “damn” in a chat room, or reactivating the accounts, that came to us. We did all that stuff. I basically concentrated on working with the email complaints and dealing with stuff that was on the numerous amount of AOL’s bulletin boards before I actually got into dealing with what the company termed illegal images.

[00:07:06] Patrick O’Keefe: When you first got to AOL and you start to deal with these problems, not necessarily just like child sexual abuse material, but also the other types of reports that you’re talking about when you first got there. How basic is the toolset that you have at your disposal? How basic were the tools?

[00:07:21] Ralph Spencer: We had an email box, we had what they call CRIS. I don’t know if anybody ever explained to me what the acronym CRIS meant, but I expect it probably had to do a Customer Relations Information System. What CRIS was is, I had a CRIS account, password. I pull up CRIS, put your screen name in CRIS, and all of your information that we got from you comes up. Your real name, address, your billing information, and your account history. I can take CRIS and cancel, warn, or terminate your account, and that’s basically what I was doing.

Also, what we had for dealing with the email complaints was we had what we called Ghost Tools. All that was was basically a bunch of canned answers that helped you cycle through the emails much quicker. Instead of having to write out an individual response to each complaint or each email that you receive because you had to basically, as long as it wasn’t somebody goofing around and whatnot, you basically had to answer each piece of email. The emails fell into categories and they had the list of canned answers on the Ghost Tools was very long. You could just pick something from the Ghost Tools and send them a canned answer.

The members realized at some point that you’re sending them a canned answer, so you’d get an email saying, “I have this problem and I want an individual customized response,” but we didn’t really have the time to do all of that for the most part because you had to get through so many emails a day. We’d send them another canned answer.

[00:08:51] Patrick O’Keefe: Yes, so as you spend time at AOL, you dig into these deeper more serious, dangerous crimes and you oversaw an automated scanning process to identify child sexual abuse material, the image detection filtering process or IDFP. Can you talk about that process and the development of it?

[00:09:11] Ralph Spencer: Yes, so much is the development of it. All I remember, we had a programmer or a developer, basically a coder, within our group who started it. He wasn’t perfect at it and whatnot. He wrote the code for it basically, so it would detect these images that once they were scanned and uploaded into the system using email. They came to me, I picked out the initial ten images that started this, that he tested with, and then it went from there.

Now, I’ve got to be honest, there’s a great period of time in-between the time when he started all of this and when the whole process actually took off. We’re talking about probably about seven years. He did the initial take on the process in maybe 2000-2001. We didn’t really get up and running with IDFP until early 2008 and there was all this time in between where I dealt with these images and whatnot in some form or another, but during all this time, I was also actually doing the technical investigation, I was also performing the technical investigation role, investigating death threats, and doing illegal compliance, and all that. Once 2008 rolled around, I became the sole person responsible for overseeing IDFP, and that’s when all of the stuff with the CSAM stuff got really rolling.

Now, before that, we had a team of people from ’95, through roughly about 2000, 2001, that dealt with the images and warning and terminating and collecting, compiling the evidence to turn over to, initially the FBI, and then the associate general counsel who ran the crime unit ended up creating a bunch of agreements with attorneys general of various states, where because we weren’t getting any feedback from the FBI, he did this. Instead of sending the stuff to the FBI, we would send it to these attorneys general, they would set up these task force for each state, and I would end up sending the stuff to the task force of each state.

Now, he didn’t get an agreement with all states, he got agreements with several states, and there were some states that were a lot more aggressive in prosecuting and pursuing this stuff than other. Among the states that I can think of California, Texas, and New York went to town on these folks and whatnot.

Matter of fact, to be honest with you, I couldn’t pull up the article now, I don’t even know where it is, but I think we made the front page in the New York Times back in the late ’90s with a situation.

We sent some stuff to the New York AG’s office, they pursued it and in doing all that, the New York Times got hold of the information and ended up that one of the people that this situation caught, I caught a night janitor in an elementary school in the Bronx. He was using a screen name on his girlfriend’s account, and, of course, he’s working at night, so nobody’s in there, using a screen name on his girlfriend’s account, and he’s using an Apple computer in one of the vice principal’s offices to do all his dirt. Thought that was interesting.

That’s how it went, but of course, when you’re dealing with a team of people doing this stuff, you got attrition. People leave because they get tired of dealing with it, or, just want to move on and do something else. It came down to where eventually, it was just me and one other guy dealing with this stuff, and that’s when everything, the volume, slowed down. By the time IDFP kicked in and got running for real, the other fellow that I was working with, he’d been laid off for a couple of years before, and then they just came and said, we get working with IDFP.

[00:12:49] Patrick O’Keefe: Let’s pause for a moment to talk about our generous sponsor, Vanilla.

Vanilla provides a one-stop-shop solution that gives community leaders all the tools they need to create a thriving community. Engagement tools like ideation and gamification promote vibrant discussion and powerful moderation tools allow admins to stay on top of conversations and keep things on track. All of these features are available out of the box, and come with best-in-class technical and community support from Vanilla’s Success Team. Vanilla is trusted by King, Acer, Qualtrics, and many more leading brands. Visit vanillaforums.com.

Just to put the obvious out there, from what you’re saying, it sounds like before IDFP, the way that you would detect these illegal images was through just manually reviewing reports law enforcement information, it was a very manual process.

[00:13:35] Ralph Spencer: Basically, we got reports from the membership. It was all the stuff that we get for- all of the images was from the membership, and we weren’t getting just reports with CSAM material, we were getting everything. It was against AOL’s terms of service to transfer pornography of any sort on the email system, all right? Initially, when we began doing that, and when I started doing that, was in November– I joined- the team that did this comprised of two people. I was the third permanent person on this team to join this team, and when we started doing it, we terminated for everything.

Whether it was child porn or whether it was pictures from a Playboy centerfold, that was the range. We terminated for everything. Then, in I think it was ’96, at this time Steve Case was running the company, he hired this guy from FedEx. I think his name was Bill Razzouk. And Razzouk took a look at the churn numbers and saw, well, there was a bunch of accounts being terminated from this one particular group. We want to know what’s going on with that.

He found, of course, once they found out what was going on, they backed up a little bit but what they wanted to do was in order to save a bunch of the membership, to save a lot of the membership and whatnot, for illegal images, which included the CSAM and beastiality, you’re terminated for that, no questions, nobody got any second chances, but as long as it wasn’t egregious, outrageous pornography, they put them on the same warning system that all the other members got, it was a three-strikes-and-you’re-out situation.

If you sent pornography regular what we call garden-variety pornography, once or twice, you got a warning letter. The third time, your account got terminated. Now, the difference between getting terminated for pornography of any sort and getting terminated for saying damn in the chat room, if you got terminated for saying damn in a chat room, you could contact the people, we had a reactivations team. You contact them and get your account back. They just made you promise to read the terms of service. If you got terminated for pornography, you didn’t get your account back. That was permanent. Nobody but the people on my team could reactivate those accounts, and we never reactivated accounts.

[00:15:48] Patrick O’Keefe: One of the things that I take away from what you said was just that a lot of these reports are coming in from the community of members, which means that the members had to see these images. Not just the staff, but they had to see it in order to report it and flag it so that you could take action on it.

[00:16:02] Ralph Spencer: That’s right.

[00:16:03] Patrick O’Keefe: You build this filtering tech, right. How do you identify the images that go into the filtering tech?

[00:16:12] Ralph Spencer: I did it myself. We started with a small number of images, they came to me. What I remember is, before IDFP process itself got up and running, when they were still constructing it and developing it, I was told to start trying to save as many images as I could find so we could start building this database. We started out with basically a few thousand images in 2008. It involved a little bit of the legalese because you have to first jump back to the terms of service. Now, if you actually go through the terms of service when you sign on to get an AOL account, nobody generally does. They scroll all the way down to the bottom and click okay. They want to go on and do whatever stuff they can do to get into getting the account and stuff.

There’s a clause in the terms of service that basically says that either the member or the company can terminate the account for any reason at any time. It also says pretty much that the account belongs to the company, all right? The account belongs to the company. Therefore, if you’re doing something with the account that is illegal, then I’ve got the right to go in and look at the stuff on your account. That’s basically how I began to build a database. I got the okay from the legal department to go into accounts that had been terminated for sending this stuff, and then go through all of their emails, and any images that I find that I deem to be CSAM and stuff like that, I save that, and then we put it in the database, and that’s how it began. It began with a few thousand images. This was in 2007, 2008. By the time I left the company in 2015, I’d built the database up to over 98,000 hash files. The way that worked was, I went in, chose the images, then in the beginning, I would give the images to one of the guys who was working with me, a go-between between myself and the developers who actually worked on constructing the process. He would convert the images into hash files. We used a huge number of hash files, but the main ones that everybody remembers and the main ones that everybody knows are SHA256 and MD5. We converted them into those hash files, and then the hash files went into the database, and the process searched against the database.

In other words, it’s not looking at images, it’s looking at the actual hash file. For anybody that knows, while I could convert the image into a hash file, I’ve been assured that you can’t reverse-engineer the process. I can convert an image into a hash file, but you can’t convert a hash file back into that image. That means that basically if all you have on your premises is the hash files, then you’re not really breaking the law.

[00:18:56] Patrick O’Keefe: To build this database, you had to personally look at each of these images before they were added. You mentioned already on this show that people were burning out of this role because they wanted to move on to something else, they got sick of looking at the images, this type of work. It’s a common story, that people burn out of these types of roles; it’s very intense. In your case, over 98,000 images, to say they can take a toll on your mental health and wellbeing I think is an understatement. This is in an era where people talk about those things far less frequently, and there was less focus on the mental health of workers. You did it. You stuck in it, continued to do it for a long time, over 98,000 images. How did you do it? Why do you think you were able to succeed in this role and stick to it for so long?

[00:19:39] Ralph Spencer: How did I keep from doing it and going crazy, right?

[00:19:41] Patrick O’Keefe: More or less.

[00:19:44] Ralph Spencer: I can tell you but it relates to a story that happened back while I was living in New York and working for Prodigy, and it involves a little girl that lived in the apartment building that, I was married at the time, my wife and I were living in. It’s not a pretty story. If you want me to go into that, I can, but I’m going to let you know right now, it’s not very pretty because it involves an actual case of actual sexual molestation on a child.

[00:20:12] Patrick O’Keefe: I don’t want you to dig into details or go into any kind of painful details necessarily, but what I’m hearing is that you saw something in your life that dedicated, that made you want to dedicate yourself to this work.

[00:20:23] Ralph Spencer: Yes, it was a motivational factor and I felt it was a situation where while I did do something and I did basically all I could in that situation, I didn’t do enough. When this came along and like I said in my email, I fell backwards into doing this, to begin with, in the first place. I saw it as an opportunity, if I couldn’t make the situation that I was dealing with in real life correct, then maybe I can do something to make a situation for one of these kids in these pictures a little bit better. That’s how I thought. Plus, it’s a thing where, I don’t know.

The best way I can explain it is if you go out and you got a job manual labor, and you’re digging ditches, you get callouses on your hands. I’m not going to say that there was a mental callous or anything like that, but I developed a way of dealing with it. You got certain things like I’d leave work and try not to think about it. When we were still doing this as a team, the guy running the team would say, all right, I know we were dealing with some serious stuff here. Everybody at AOL generally got near 45 minutes to an hour for lunch. We’d take two-hour lunches, go out, walk around. We did stuff like team days before people really started doing them. We went downtown in DC one day and went to the art gallery. The logic for that was like, you see ugly stuff every day. Let’s go look at some stuff that has cultural value or has some beauty to it and we’ll stop and have lunch at a nice restaurant, that kind of thing. It’s stuff like that that initially, we would do to take somebody’s edge of it is. Basically, once it got to be an IDFP yes, it was just me, but you just find a way to deal with it, and I guess one of the ways, which is actually going to seem weird, but it actually got me through it, first thing was I read a lot.

I found an author’s name who’s Andrew Vachss, V-A-C-H-S-S. At one point, I think his wife was either a district attorney in Queens or an assistant district attorney in Queens. He’s a lawyer and he had a special practice. He only represented children who were victims of sexual abuse and he did all this pro bono, but of course, for him to do that, he needed a way to make money so he wrote books on the side. Basically, his books featured a character that basically went and rescued children out of these types of situations. I actually met him once. There used to be a chain of bookstores in the DC area called Olsson’s. He came to promote one of his books at one time and instead of doing a reading from the books, which he said would generally he tried to do, but it freaked people out, he just gave a little spiel about the book and what he did, and he opened the floor up for questions and people just ask questions. At the end of the question and answer period, he’d sign the books.

I went up to him and told him exactly because I was doing this stuff by this time, I was working on the team. I told him exactly what I did and he gave me that, “Oh, you poor thing,” pitiful look. He’s like, “You see the stuff that’s going on?” I said, “Yes, I did.” He was like, well, thanked me for doing what I did and he said, “Well, you got a book, I’ll sign your book.” He signed a book, “Happy hunting.”

[00:23:32] Patrick O’Keefe: Yes, wow.

[00:23:33] Ralph Spencer: What’s up? All right. Then the other thing was, I became a huge Harry Potter fan, which I know sounds strange, but–

[00:23:40] Patrick O’Keefe: I’ve read all the books, seen all the movies.

[00:23:41] Ralph Spencer: I looked at it like this, there’s this one kid, he’s got the meanest ugliest wizard in the world coming down on him and he finds a way to fight back. I figured there was some inspiration I could get with.

[00:23:54] Patrick O’Keefe: For sure. Beyond the massive mental weight of this type of work, there can also be repercussions in your personal life. I know before the show, you referenced some incidences that happened to former coworkers that led you to create a more low-profile online persona. It’s not just what you have to deal with day-to-day doing the work, it’s after people get held accountable, it’s a hard job to turn off of sometimes, too.

[00:24:15] Ralph Spencer: Yes, it is. There are situations where it’s not often, I can only think of one instance, but there was a member or a coworker of mine who actually got death threats as a result of this. It wasn’t exactly because he was going the work, it was an offshoot of some of the stuff that we were doing. It’s not like this is the easiest thing in the world and then you turn on and you have to be concerned about something like that. Yes, it’s more like wanting to keep a low profile for doing this kind of thing.

[00:24:44] Patrick O’Keefe: Not to do with children being abused, more mundane example. We recently had a president who would tweet at specific staff members of major social media platforms, blaming them, that person for the problem or and talking about individuals, which of course, led that individual to receive all sorts of abuse, all kinds of things.

[00:25:07] Ralph Spencer: You don’t want to get me started on him, but yes.

[00:25:09] Patrick O’Keefe: [laughs] Yes, same here. One thing I do want to ask you though is, how did the IDFP database differ from the database maintained by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children? Did they work in tandem or are they similar? What’s the difference?

[00:25:25] Ralph Spencer: Now, we get into something that may be just might be a little bit more involved, and it’s funny that you should ask that because I’ve been following the situation with Apple and what they’re trying to do with iCloud. Basically, it sounds like they are using the same type of technology that we used on IDFP. Let me get back to your question. First of all, IDFP was our thing. As far as I know, I don’t know whether the technology for the scanning thing, of course, everybody scans for everything, but the developers at AOL took it and tailored it specifically for this particular instance, this particular situation.

Like I said before, the database that we use for IDFP, they were all hand-picked by me. The reason for this is the thing that makes IDFP scanning different from say, Microsoft Photo DNA, which we also use and I will get into that in a minute if you want, is that IDFP scanned for the image and it was an exact match. I got one image in the database. Somebody wants to send a copy of this image back through the system, all that person had to do was go in and change one characteristic. Basically, all you do is go in and change a pixel. That creates an entirely new image that will get by IDFP until I see it again and add it to the database.

Yes, I had several probably, in some cases, numerous copies of the same image. You want to make the image smaller. You want to make the image bigger. You want to make the image lighter. You want to make the image darker. You want to try to change the color of the victim’s eye. Any one of those things means that it creates a brand new image for IDFP. That’s one thing to how IDFP differ.

Also, we were really wary of taking databases or images from say, NCMEC, or from say, the FBI because there is, and to this day, I really don’t quite understand the way that the situation works, but we wanted to avoid being called or being referred to what’s known as an agent of the government. Apparently, if you take images from NCMEC who works closely with law enforcement, or from any law enforcement agency, you can be accused by a defense attorney of being an agent of the government.

I think what this has to do with is if you agree to work with the government, then there’s a whole thing about the Fourth Amendment and search and seizure, that kind of thing. It’s like, you’re an agent of the government, so there’s a possibility that the defense attorney can get somebody off on this situation by basically claiming that his account, even though the account belonged to AOL, was illegally searched by you and you’re acting as an agent of the government.

By creating our own database and by our going in and looking at these accounts and whatnot, we’re not involving any form of law enforcement. The way our situation work was, I scan the images in the IDFP, IDFP scans the emails. It catches something that it sees that’s in the database, it packages a report which includes the image, the email that the image was attached to, and a very small amount of identifying information into this report.

The report is then automatically, sent by the process to NCMEC. NCMEC looks at it, decides if it’s something that they can run with, and if it is, then they take the small amount of identifying information that we supplied. By that, they’re able to get an idea of which local jurisdiction to send the report to. They send the report to law enforcement in that jurisdiction, law enforcement then looks at it, says, “Well, yes, we think we can make the case with this.” Then they go back and that’s where the whole compliance stuff starts coming in.

Law enforcement sends the subpoenas, search warrants, the preservation orders to get this account information from us, and that starts the whole ball rolling. That’s basically, how it works in a nutshell.

[00:29:31] Patrick O’Keefe: What you’ve described as more or less how Apple laid out their news. I was curious to get your perspective on it just because you’ve done this tough work for years. I know that you take privacy seriously as well. Apple’s announcement in August was that with new versions of their operating systems, they had planned to introduce a feature where, when an image is uploaded to iCloud, I’m going to quote directly, “an on-device matching process is performed for that image against the known CSAM hashes.” Then then when a photo matches a certain threshold, Apple would manually review the report to confirm a match. If a match is confirmed, they would disable the user’s account and send the report to NCMEC.

When this news came out, as I’m sure you know, there was a lot of uproar about potential violations of privacy, but I also heard from a contingent of community moderation trust and safety veterans, like a friend of the show, Derek Powazek, who said that the NCMEC database is a carefully vetted database, and that not only would the move save lives, but that it would also help protect people who do this work in trust and safety by not forcing them to view the same photos over and over again, potentially traumatizing themselves again, over and over again.

To quote him, he said, “Content moderators have actual PTSD from doing their jobs. We should have more programs that block content based on its signature so humans don’t have to see it.” After the response to their announcement, Apple decides to push back the rollout indefinitely. Given your experience, I was interested to see what side of the discussion you fall on?

[00:30:57] Ralph Spencer: Well, first of all, I think it was a lot of confusion because people thinking that Apple is going to go on your iPhone, and just look at everything on your iPhone, and that is not how it works. It’s on the iCloud account, which is basically the same thing, you can compare that to an AOL email account. iCloud is owned by Apple, it’s their world, you just live in it by using the space.

[00:31:16] Patrick O’Keefe: Yes. They have confirmed that if you disable iCloud, your photos won’t be scanned in this way. They’ve confirmed that.

[00:31:20] Ralph Spencer: Exactly. Just like you kill your AOL account, that’s it. The thing about it, as far as that’s concerned, I’m on the side of scanning, because they get this stuff, it’s up there, it’s Apple’s domain. If you’re dumb enough to put the stuff up in there and they can scan for it, then you get what you pay for. Basically, that stuff is going to be all over the place anyway because I think when we started out, it was a small problem.

There’s an article, a series of articles in the New York Times a couple of years ago, September of 2019, as a matter of fact, where they actually talked about and reported on the issue of CSAM. They said it has ballooned up now to some 45 million images I think per year, or something like that, and they basically say that NCMEC was overwhelmed. If you want to do this, I don’t have any problem with Apple doing it, basically what I’m trying to say because the way that they’re going about it sounds almost verbatim like the way we went about it with IDFP.

We’ve got a specific area that we stay within, we don’t go outside of that area, and we scan just in that area. Nobody’s going on your iPhone, and nobody’s going on your Mac to do this, but if you load this stuff up in iCloud, it’s open season. By the way, just so I wanted because you mentioned how Apple would terminate the person’s account, I left out the fact that when IDFP, as part of the automated process, once IDFP scan and identified the account, before it sent the account to NCMEC, it automatically terminated the account with a non-reactivatable term code. I didn’t want anybody to get the idea they could just send the report in and this person was going on doing all the dirt they wanted to do until they got caught by the cops. No, the process terminated the account as well as part of the actual policy.

[00:33:11] Patrick O’Keefe: Thanks for that. Yes, it’s interesting to hear your perspective, just because like, I totally get the privacy advocacy perspective, even if it’s based on, as you said, thinking Apple is going to look at your phone, but I think it’s important to hear from people who’ve actually had to look at these types of images as part of their job and hear that perspective. Again, this podcast is biased in a little bit to them, people who do this work, but we’re people too, and we factor into this world and this online world and protecting people, protecting kids.

If there’s a way where we can balance concerns around privacy, but also the well-being of people who are in this line of work, and inevitably, have to look at some of these images, but if we can make it a little better, make it worked a little more efficiently both for the systems, no one wants false flags, no one wants that type of thing, but good systems and also take care of people, then I find myself leaning to that side as well.

[00:34:04] Ralph Spencer: Yes, no problem with that whatsoever. Yes. My understanding is now that it’s mandated by, I don’t want to say all companies, but a lot of companies that I’ve heard of is that now they have a policy where if somebody does this type of work, they make psychological counseling available to them. I know for a fact that they do this with NCMEC. I think it’s to the point to NCMEC where they have somebody on call 24 hours a day. If you wake up with a bad dream in the middle of the night, there’s a phone number you can call and I think they are required to periodically go sit down and talk with a trained professional about the stuff that they see.

That never really did go on while I was at AOL. There was mention of it, but it never got beyond the mentioned point. I’m not sure now. I believe they may have implemented something for the one or two people who I think are still there doing the job now, but I’m not sure.

[00:35:00] Patrick O’Keefe: I think the industry has made progress, but more to go. Your work contributed to countless arrests and convictions. Before the show, you shared with me a document that highlighted numerous cases that you had been involved in. It was quite a list of people, law enforcement officers, elected officials, and so on. I was curious to ask you, what are the cases that stand out in your mind if any?

[00:35:20] Ralph Spencer: Okay. There were actually three, but unfortunately, I was only able to document two of them because the last one happened in 2014. As I mentioned in the email, the way that I acquired this list is that at AOL, you have to write your own performance review. Every year, I generally had to search the web because a lot of times, the cops and law enforcement, they wouldn’t let us know what happened. They might let NCMEC know, and then NCMEC would let us know from time to time of its success and whatnot. Generally, I had to go in and this stuff, it never got back to us, but a lot of this stuff generally makes the media. That’s how I find it. Then I write out a little blurb and put this on a performance review.

The three that stand out in my mind, there are two of them which are basically the same thing. They both involve little girls who were being actively molested by, one was a person in a neighborhood, and the other one was by her own stepfather. Both of these people had images, they were trading images on AOL. IDFP caught one of them and I think the other one may have been manually reported to me.

Anyway, the stuff got packaged up and sent to NCMEC. NCMEC went through the proper procedures, they went through with law enforcement. When law enforcement served a search warrant on each of these guys, picked up their computers, went through the stuff on their computer, they found what looked to them to be like homemade images. That’s how they found this guy who was basically actively raping this child in his neighborhood. That’s how they found the stepfather because they sent images and all that.

We got an email from NCMEC, basically stating, describing one of these situations. An email basically said, “Due to the evidence you guys turn over to IDFP, you’ve actively managed to save a little girl from an active molestation situation.” That’s the kind of thing that sticks with you.

Then the other thing, there was a case where a guy was managing the team I was on actually sent an email up the chain saying basically that Ralph caught a fed. What happened was the head of the Miami, Florida office for an Immigrations and Customs Enforcement Agency, ICE. This was back in April of 2011. We caught the guy who was running the Miami office of ICE, he was sending child pornography. The guy’s name is Anthony Mangione. If your listeners want to Google that up, I can spell the name and you might still be able to find that because I think this stuff is still in there.

[00:37:51] Patrick O’Keefe: Yes, I found an article on it.

[00:37:52] Ralph Spencer: In the article, it probably said something to the effect of AOL cooperated fully with law enforcement in this case. What that meant was that either me or IDFP, and it’s synonymous, sent them the image that started the whole thing. That one even more so than the one with the little girls and whatnot, that one set me back a little bit. Because I know that initially, a few years before, before IDFP, before we got started with IDFP, there was a coworker of mine that came in and she found his huge cache of CSAM that came from an AOL account in Germany. Because at that time AOL, we had accounts, branches in all countries all over the world. We have one in Japan, Germany, France, the lot.

We couldn’t do anything with it. The FBI and local law enforcement couldn’t do anything with the stuff from that account because it was a European account, we had to call in ICE. We got an official, the high ranking official or I thought it was a high ranking official from ICE, come in one day. He spoke to the entire group, and oh, we’re going to do this, we’re going to do that, and nothing ever happened. What that tells me is that this guy in Florida had access to probably untold number of images that he could play with, trade, and do all that kind of stuff.

It just so happened that he sent an image over his AOL account that we had in the database. I remember asking the guy who started the team that I was on, who went on to become an expert witness. He worked in the legal department, and his job basically was to go around the country and testify at all the trials explaining how the technology that caught these images work. I said, “Yes, I saw this. I got an email about this guy from ICE down in Florida, was that us?” He’s like, “Yes, that was you.” I was like, “Really?” He’s like, “Yes, that guy’s in a lot of trouble.”

[00:39:41] Patrick O’Keefe: Wow. This document that you have, you’re documenting the cases that you hear about that come back to you because you don’t necessarily learn the results and all of your work, so when you do you want to note it for your own performance review. Discussions around trust and safety metrics persist in substantial ways to this day, and people are still I think, in a lot of cases trying to figure it out. When you were doing this work, were there any metrics that were important? Or were there things that mattered to the people who decided how the money was spent and who got to keep their job?

[00:40:08] Ralph Spencer: There’s a question. Yes, and something that I think I meant to mention and overlooked, the thing about this is, and I think one of the ways yes, that I managed to stay in the job for so long because you got to understand that this is the tech industry. At AOL, they did layoffs yearly. They used to do them en masse in the beginning, the first five or 10 years when I was working there, then they got a little bit more subtle with it.

The reason that this became such an issue was that there was a statute in the federal government where companies who learned about these types of images, knowing that they’re on their systems, they could be fined for not reporting these images. I believe the fines went something like for the first one to two days that the image is not reported, you will be fined by the federal government, it was $150,000 per image per day for the first 2 days. On the 3rd day, if you still fail to report it, the fine doubled and it became $300,000 per image per day.

It would be in the best interest of the company bottom line-wise to go ahead and try to do something about this because otherwise, you don’t want to get fined for this kind of stuff. Because let me put it this way, when members got the ability to embed images in the email, in other words, not send them as an attached file, but just put them right down to the text of the email, these jokers that I’ve basically dealt with, they went buck wild with.

I can remember on several occasions, going through emails that had over 100 images in them. Multiply that, say that’s been on your system and you’ve known about it for 3 days, you’ve got 100 of these images, they’re all CSAM images, $300,000 per image, do the math. It’s necessary that these companies have somebody at that point to do something like this because it’s good for their bottom line.

They’ll tell you yes, it also makes it look like you’re a good corporate citizen, and all that kind of stuff, which was something I used in the performance review, but I made a point with each performance review, I mentioned the fact about the fines because that will be something that grabs somebody’s attention. What I didn’t tend to mention is that nobody really enforces these fines, or at least while I was doing it, nobody really enforced the fine.

There was nobody coming around saying well we understand that you’re getting these images. How often are you reporting the images and are you reporting the images on a regular basis? Nobody’s bothering to deal with that, but that’s one reason why they would need somebody around to do this stuff. Be in it for that time, from 2004, 2005 on, I was the main person dealing with those issues. That’s basically I think how I kept the job for so long.

[00:42:51] Patrick O’Keefe: Yes, I mean, even if it wasn’t enforced the threats there, right?

[00:42:54] Ralph Spencer: Yes, all the threats are there.

[00:42:56] Patrick O’Keefe: If you neglect it, someone’s going to notice, and then you never know. You get the right scrutiny, the government involved, the fine can be substantial then, so you’re saving them money I guess is one way to look at it.

When we chatted before the show, you told me that you weren’t a huge fan of social media, and in particular, Facebook on which you deactivated your account, and I’m going to quote you here, “After seeing the never-ending array of shenanigans Zuckerberg and Co. seem to constantly be able to conjure up.”

In September, the Wall Street Journal, led by reporter Jeff Horwitz, who’s been on this show before, published a series of blistering articles about Facebook and their poor handling of moderation, trust and safety issues. We’ve also seen whistleblowers like Sophie Zhang, who’s been on the show as well, and Frances Haugen, the key source for the Wall Street Journal’s reporting. Have you been following any of these stores?

[00:43:39] Ralph Spencer: Yes, I have, particularly the whistleblower story.

[00:43:42] Patrick O’Keefe: What do you think about them?

[00:43:42] Ralph Spencer: I think Facebook got too big, too fast. They’ve got what, billions of members?

[00:43:47] Patrick O’Keefe: Yes.

[00:43:47] Ralph Spencer: All right, you got to understand that when I was at AOL, our highlight was I think when we got to six million, now, I know we made more, we got more than six million, I think we got into the double digits, but I don’t think we had anything near what Facebook has. When you get something that big, first of all, it’s going to be hard to corral anything that size, all right? Dealing with content management, I think you know, I know, your audience knows that it’s a high turnover kind of thing, especially at places like Facebook.

My understanding of Facebook is just hires independent contractors. You do that for that little bit of money with no appreciation, you’re going to burn out pretty quick anyway, and you’re basically not really going to care what gets by you and what doesn’t because you’re not being properly compensated, you’re working long hours, and you seeing ugly stuff. Why should anybody who’s doing that stuff at Facebook really care about what they’re doing?

The other thing is, though, what I have a problem with Facebook is they look like they’re actively trying to cover this stuff up. We made no bones about what we did. Now, in the beginning, when I started out on the team, the guy running the team basically said, when somebody asked you what you’re doing, just say we’re doing stuff that helps the company because AOL was trying to get off the ground and they were working as a family-oriented service, but we had the situation somewhat under control.

I think Facebook, Zuckerberg is running around talking about how he’s trying to get the world closer together by communicating, increasing the lines of communication. A lot of these lines just lead to destructive ends. Facebook, it’s like we were talking about earlier with the former government employee. That’s just creating a whole lot of division and they’re using Facebook to do this kind of stuff. Plus Facebook had a private messaging feature, I’ve forgotten exactly what it’s called, a messaging feature which Zuckerberg said he was going to take private, and he admitted that that would be a boon for people dealing in child sexual abuse material. If you knowingly are going to promote something like that, then I got a problem with you already. That’s just blatant.

[00:45:51] Patrick O’Keefe: I think I know what you’re referencing. Back in 2019, during a company Q&A, after Facebook had announced plans to encrypt the company’s messaging services, Zuckerberg had received some criticism and he defended the move but also acknowledged that it would mean, “You’re fighting that battle with at least a hand tied behind your back.” I think there may have been a time when I considered Facebook to be beneficial in some ways or in some countries. You look at the countries under an authoritarian rule, a way to circumvent that rule, talk to other people. There may have been a time when I thought that was a positive–

[00:46:29] Ralph Spencer: Yes, the Arab Spring.

[00:46:30] Patrick O’Keefe: I no longer believe that. I think that, from the reporting that we’ve seen, they’ve become the tool of authoritarians. Sophie Zhang, in particular, talked about how they basically are more interested in appeasing local governments and operating Facebook in those countries, than they are in actually building something that resembles a healthy platform in the countries where they operate where there is less money, where they don’t prioritize trust and safety resources, where they may not even have people trained in all of the dialects of the languages that are spoken in those countries, so they can’t adequately moderate what’s happening because they simply threw up a website and threw a few dollars behind it and just looked at it as one more way to grow. One more way to get to 3.175 billion or 3.185 billion, and it’s really out of control.

I think you said it in the fact that they scaled too fast without regard for safety in order to appease investors, make money, generate revenue. I don’t think monopolies are good, but I’m not someone who’s policing around for monopolies. It’s not my area of interest, but there is a point where Facebook I think becomes a harm to society because of their scale. I don’t have the answer, but I just can say that I don’t like it. I don’t like what’s happening right now at Facebook. I don’t think it’s good for society anymore.

[00:47:42] Ralph Spencer: Exactly what you were saying about monopolies. I’m old enough to remember the whole thing where they broke up the Bell telephone companies into various pieces and whatnot. I don’t really know that doing that with Facebook is going to help because all right, it’s Facebook and it’s Instagram, and they’ve got WhatsApp. Even if you broke those up into separate entities, you still have Facebook, and in my opinion, Facebook is the part of the company that’s generating the most problems, all right? Because that’s responsible for the divisiveness, and that’s the tool that the former government employee along with Twitter was able to use to further his means.

I don’t see how they can actually break up the Facebook part of Facebook, the bulletin board, or whatever, that interface that they use for that. You can section off Instagram and WhatsApp and all that and put them over and let somebody else run that, but the whole problem, in my opinion, begins and ends with the actual Facebook application.

[00:48:39] Patrick O’Keefe: Yes. It’s an interesting point because if you break off Facebook from the other apps, they still have the amount of people on Facebook.

[00:48:44] Ralph Spencer: Exactly. You’re still going to have the three billion people or however many billion people there is on Facebook and they’re all going to still be causing trouble.

[00:48:50] Patrick O’Keefe: Facebook has taken this tone recently that I find a little bothersome, curious what you think, where they’re basically saying, please regulate us. This started maybe, I don’t know, several months ago when Zuckerberg, I think he testified in front of Congress and said that they would be open to regulatory changes. He specifically mentioned Section 230, where some of the other executives like the CEO of Alphabet and CEO of Twitter didn’t go that far. They didn’t say those exact things, where Zuckerberg was like more or less, you can regulate us.

There’s now advocating for this regulation, including reform to Section 230. I’ve personally seen Google AdWords ads on search results. If you search for Facebook Section 230 regulation, you get an ad that says, “We care about safety. We want to be regulated,” basically. “We encourage internet regulation.” I’ve also heard an audio ad on Spotify and also a video ad on a video streaming service saying exactly the same thing. They have this ad push basically saying we need new internet regulation, change Section 230. What do you make of that?

[00:49:48] Ralph Spencer: That whole thing about how the internet has grown and the individual they show you than what we saw, I used to see on AOL all the time, the little dancing baby and all that. Now that’s gotten so far-

[00:49:59] Patrick O’Keefe: Exactly.

[00:49:59] Ralph Spencer: -so far past you know basically, they’re trying to save their own neck, but the thing about it is I don’t know if that’s such a wise idea for them to do. They might be better of siding with the people at Google and Twitter and just shutting up about it. Because I personally think that I’ve looked at the stuff on your site and seeing what I think is– I got wind of your opinion of Section 230 and I think maybe we might differ a bit. I think that it needs to be amended, and I’m looking at it just from the standpoint of what I used to do for a living.

Section 230 is what helped all of these people, all these companies hide behind not having to do anything about the child porn problem. That’s how it got so big in my opinion. They could hide behind Section 230 which has basically a safe harbor clause. If we don’t know about it, if somebody doesn’t tell us about it, we don’t have to do anything about it because it’s not our responsibility. It’s the responsibility of the actual person who’s using our platform, but he’s the one doing the dirt, so he’s the one that’s responsible. If nobody tells us about it, then we can’t do anything about it.

I think that’s a load of crap. Yes, it’s saving all of these companies money because they don’t have to hire a whole army of content moderators, but the fact of the matter is I’ve seen and I have been because I’m currently not gainfully employed and I’m looking for gainful employment. I’m doing basically just consulting work and whatnot, but I’ve seen a couple of companies advertising, Google being one of them, advertise for somebody to deal specifically with this stuff. They’re calling the position child safety engineers or child safety moderators and whatnot.

Basically, what they’re looking for is somebody to deal with the child pornography or the CSAM issue. Now, because I think that’s all because they’re looking and they’re seeing that there’s going to be changes made to Section 230 and it may come to a point where they can no longer hide behind Section 230 on this issue. I’m waiting to see what happens with that because I’m really curious as to how that’s going to work out.

[00:52:00] Patrick O’Keefe: I think we do differ, but I’m open to other opinions on this show also, so that doesn’t bother me at all. Section 230 does have some exceptions including for Federal Criminal Law, which includes CSAM. There are mechanisms available and some would argue those mechanisms should be adjusted, there might be a need of adjustment as opposed to touching 230.

It’s important that those things be fully explored as we think about 230, but for me, 230, where I come at it from is really– My long-term concern with Facebook has always been that Facebook would do something so catastrophically bad that it would hurt the ability of small online communities and platforms to start up and exist. I was a teenager running a forum out of my home. That’s how I got started. It was a small community, I took care of it, I didn’t have this problem. Most online communities that exist throughout the world don’t really have this problem. They operate in different subject areas, they have moderation figured out. They’re at a scale where they’ve responsibly grown.

Then you have Facebook come along. I totally get what you’re saying about AOL. I see how that could be the case, how Section 230 could’ve empowered them. It also empowered them to moderate and to take some responsibility for their platform. Going back to the Prodigy lawsuit that helped create 230, didn’t like the criticism from the guy from The Wolf of Wall Street, so he sued, and then they made a law right away for Section 230.

I think for me, I’m always open to ideas for amending it that make sense and also don’t seriously harm the me who was 13 starting a forum about sports. I think that’s where the balance has to be found. I am not necessarily for amending it. I’m not 100% against it. I’m interested in a good idea that might be effective. I think a lot of people who argue against it feel like amending it won’t actually move us closer to the goal, and that other avenues should be explored, but it is one prong of the online legislative environment and it does say, as you said, that the person who writes something is responsible for what they write. I think people do abuse that in some cases to-

[00:53:59] Ralph Spencer: Greatly.

[00:54:00] Patrick O’Keefe: -moderate slowly or moderate poorly. I think those that do that really represent a harm to online community builders in general. That’s unfortunate.

[00:54:10] Ralph Spencer: That’s true. There are some companies that were back when I was at AOL, who were actually trying to follow our lead and deal with that shit with that particular issue, dealing with the CSAM. One thing that I didn’t mention about the IDFP database was we made that database, we were in, I think what was at that time called the tech coalition over at the National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children, NCMEC. They had a tech coalition.

As part of that tech coalition, I think the other companies– How many other companies involved. Yahoo was in there, Google was in there, and this company called United Online. I forgot who they basically represented or what their name brand was and whatnot. Verizon got in on it. We made the IDFP database available to all of these companies through the tech coalition. Basically, I just upload every week I updated it, found new images, and the database was updated on a weekly basis. Then after I updated the database for us, then I voted, we had FTP sites that Verizon and all the other companies could get on and access the updated databases and whatnot, and I know that before I left, Verizon actually had three separate FTP sites that I uploaded stuff to. I’m figuring one was probably because they offered email accounts with their files. Then it was probably also something having to do I’d say with the cell phone service, then I for the life of me can’t figure out what the third one was for, but we made that available through the tech coalition at NCMEC.

The other thing and this is as basically as an aside and doesn’t really have anything to do with what we were currently talking about, but you mentioned the lawsuit that occurred at Prodigy. If I’m not mistaken, that occurred by something showing up on their Frank Discussion board, right?

[00:56:00] Patrick O’Keefe: Yes. It was one of the people at Stratton Oakmont, which was the law firm in The Wolf of Wall Street, someone was criticizing him on Prodigy, I think it was a message board, and they didn’t like it so they sued Prodigy.

[00:56:13] Ralph Spencer: If It was the Frank Discussion board, I was the one that supervised the managers who worked on that board in the evening. I found that interesting. Also, that board and the way that it came in, what they were doing with it at Prodigy eventually led to Prodigy’s downfall and ended up- that’s how AOL became the number one online service for a while, right after I got there. I found that interesting. In the book that Kara Swisher wrote back in the late ’90s documenting the rise of AOL, she actually mentions the situation with the Frank Discussion board. I found that to be ironic. I know that’s off track and everything.

[00:56:50] Patrick O’Keefe: That’s internet history.

[00:56:51] Ralph Spencer: Yes.

[00:56:52] Patrick O’Keefe: Ralph, this whole conversation has been, I think, a history lesson in a lot of ways. I’m grateful to you for taking the time to chat with us today to share your experience with us. I really appreciate it. Thank you.

[00:57:02] Ralph Spencer: No problem. Thank you for letting me come on and just get all this stuff off the top of my head.

[00:57:07] Patrick O’Keefe: My pleasure. That is what we do every episode.

[00:57:10] Ralph Spencer: Well, it’s not a whole lot of people who want to hear all this stuff. Anytime I get a chance to talk about it is greatly appreciated.

[00:57:18] Patrick O’Keefe: We’ve been talking with Ralph Spencer who is a freelance trust and safety consultant. You can find him on LinkedIn we’ll link to his profile in the show notes.

For the transcript from this episode plus highlights and links that we mentioned, please visit communitysignal.com. Community Signal is produced by Karn Broad and Carol Benovic-Bradley is our editorial lead. A special thank you to David Flores for his contribution to this episode. Stay safe out there.

[music]

Your Thoughts

If you have any thoughts on this episode that you’d like to share, please leave me a comment, send me an email or a tweet. If you enjoy the show, we would be so grateful if you spread the word and supported Community Signal on Patreon.