“If a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken.” So says the

in 1982, and widely adopted in law enforcement circles.

Though the theory was created with crime in mind, it has been adopted by many industries and vocations, including online community. I have seen it come up numerous times in our industry and, in talking with other veterans of the space, we’ve been applying it for quite a while.

Broken windows policing has plenty of critics and defenders. Depending on who you talk to, it has either contributed to the reduction crime or served as an enabler of oppressive policing (or both). Dr. Kelling argues that zealotry and poor implementation are the problem, and that leniency and discretion, both vital to good community policing, have been lost in the shuffle. He boils the theory down to the “simple idea of small things matter.” Plus:

Kelling has practiced social work as a child care worker and as a probation officer and has administered residential care programs for aggressive and disturbed youth. In 1972, he began work at the Police Foundation and conducted several large-scale experiments in policing—notably, the Kansas City Preventive Patrol Experiment and the Newark Foot Patrol Experiment. The latter was the source of his contribution, with James Q. Wilson, to his most familiar essay in The Atlantic, “Broken Windows.” During the late 1980s, Kelling developed the order-maintenance policies in the New York City subway that ultimately led to radical crime reductions. Later, he consulted with the New York City Police Department in dealing with, among others, “squeegee men.”

[00:00:00] Announcer: You’re listening to Community Signal. The podcast for online community professionals. Tweet as you listen using #CommunitySignal. Here’s your host, Patrick O’Keefe.

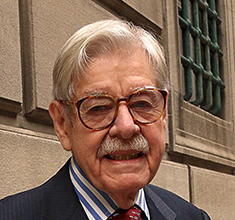

[00:00:20] Patrick O’Keefe: Hello, and thank you for joining me for this episode of Community Signal with our guest Dr. George L. Kelling, co-creator of the broken windows theory.

Voting has opened for content ideas for South by Southwest 2018. I submitted a presentation that is partially based on two episodes of the show. The first, we did in February, about how IMDb had closed their 18-year-old community with only two weeks notice, and the second, last month, covered Photobucket’s sudden change that led to potentially billions of images across the internet being broken.

My proposed talk, Build a Community for 18 Years, Kill it in 2 Weeks, will discuss the closure of online communities and how to treat your members and their contributions with respect. It’s not enough to know how to start; you have to know how to finish. If you like to support this idea, your vote will be greatly appreciated. Visit panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/75641. To make it easier, we’ll include that link in the show notes on communitysignal.com.

Thank you to our seven supporters on Patreon, including Serena Snoad, Dave Gertler, and Rachel Medanic. If you find value in our show, please consider becoming a member of our inner circle at communitysignal.com/innercircle and you will see bonus clips from the show and early access to future guests.

Dr. George L. Kelling is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a professor in the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers University, and a fellow at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. Dr. Kelling has practiced social work as a child care worker and as a probation officer and has administered residential care programs for aggressive and disturbed youth. In 1972, he began work at the Police Foundation and conducted several large scale experiments and policing. Notably, the Kansas City Preventive Patrol Experiment and the Newark Foot Patrol Experiment.

The latter was the source of his contribution with James Q. Wilson to his most familiar essay in The Atlantic: “Broken Windows”, which spawned the broken windows theory. In that essay, Dr. Kelling summarizes the theory as such, “At the community level, disorder and crime are usually inextricably linked in a kind of developmental sequence. Social psychologists and police officers tend to agree that if a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken.

“This is as true in nice neighborhoods as in rundown ones. Window-breaking does not necessarily occur on a large scale because some areas are inhabited by determined window-breakers whereas others are populated by window-lovers; rather, one unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing.” Kelling is co-author with his wife, Catherine M. Coles, of “Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in Our Communities” (from 1998). He holds a BA from St. Olaf College and MSW from the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee and a PhD from the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Dr. Kelling, welcome to the program.

[00:03:06] George L. Kelling: Thank you for having me.

[00:03:08] Patrick O’Keefe: It’s a pleasure. Our show is about digital communities, spaces online that resemble face-to-face brick and mortar communities. They have their own structure, their own social norms, governance, just like a town might, and they have community guidelines which are laws in a sense. They also have people who violate those guidelines and enforcement mechanisms for when that happens.

Now, good community management is a lot of behavior modeling and signaling. If you allow a certain behavior, you attract more people who behave that way and your community becomes known for that behavior for better or worse and for this reason, the broken windows theory is pretty well-known in our industry and has been for a long time. In putting together this episode, I reached out to five veterans of the industry, all who have been working in it for 17 years or more, and four out of five were familiar with broken windows.

Before I contacted you, to invite you onto this show, were you at all aware of our industry or the fact that we’ve been applying your work for such a long time?

[00:04:04] George L. Kelling: Yes. I’ve had a general idea. I can’t say specifically I was familiar with it, but broken windows has affected so many enterprises: from education to nursing, to other kinds of preventive health, etcetera. It’s not surprising to me but I can’t say that I was familiar specifically.

[00:04:22] Patrick O’Keefe: Have there been any industries that applied it that you were really surprised by?

[00:04:26] George L. Kelling: No, not really. I can’t say that I have been. There’s a genetic, simple idea there that small things matter and once you start from that simple idea, that can spread into a wide variety of industries ranging from private security matters to private enterprise to the whole private sector to the public sector. So, no, I haven’t been particularly surprised.

[00:04:50] Patrick O’Keefe: I don’t know if you spend a lot of time online: in online community or on social media or Twitter or anything like that, but do you have any thoughts about how your theory might apply? About it being used in virtual spaces instead of physical ones?

[00:05:03] George L. Kelling: I can’t say that I’ve really thought a whole lot about that. It’s only recently that I’ve become somewhat familiar with Twitter and I haven’t been involved in social media. I use the internet a lot but I’m of a generation that picked up on computing and social media quite late. I will celebrate my 82nd birthday this year, so I haven’t been really at the edge of social media news developments.

[00:05:27] Patrick O’Keefe: I wrote a book in 2008. Looking back, more than nine years later, there are things that I would like to change or add if I could. I was curious when you look back and think about how broken windows was introduced in the article in The Atlantic in 1982, is there anything that you wish you could add in there?

[00:05:45] George L. Kelling: I think when you talk about reading something even — Like you say, your book, nine years ago, you have to look into the eyes of that particular period. What was the context at the time and what could’ve been said? It seems to me that if one reads, especially the second half of broken windows, the 1982 publication, that was struggling with the whole set of issues: how do you maintain justice, how do you do this well, what are the possibilities for overreach. They’re all there in the article. I really don’t see how we could’ve changed it much.

There’s the one section that Jim Wilson, my co-author and I struggled with a little bit, where I talk about an officer wanting to kick ass. The question was whether we include it in the story or not. I was interested in putting it in because it pointed ultimately to the dilemma that officers face when they’re asked to do something that they can’t do or aren’t trained to do properly and the problems that it creates for officers.

I don’t think we are explicit enough in terms of that particular event in the original article, and that, I would context a little bit better. But again, I’m looking at that through 2017 eyes, not 1982 eyes or when that was going on.

[00:07:01] Patrick O’Keefe: In online communities, the person who enforces the guidelines or the laws as they were is often referred to as a moderator. On a community I manage, two of my six moderators actually work in law enforcement. It happened by accident, we didn’t plan it. Maybe it’s a role that makes sense for them online because it matches well with their offline profession.

One is a patrol officer in Kansas and another, Alex Embry, who has been a guest on the show, is a SWAT Team commander and training sergeant outside of Chicago. When I had Alex on the show, he said that officer discretion is often the hardest thing to teach new recruits. I was reminded of this by something you told PBS Frontline about your thoughts when you began to hear about police departments across the country announcing a broad adoption of broken windows as a policy.

You said, “You’re just asking for a whole lot of trouble. You don’t just one day say, go out and restore order. You train officers, you develop guidelines. Any officer who really wants to do order maintenance has to be able to answer satisfactorily the question, ‘Why do you decide to arrest one person who is urinating in public and not arrest another?’ If you can’t answer that question, if you just say, ‘Well, it’s common sense,’ you get very, very worried.” How should an officer come to their answer to that question? What does that training look like?

[00:08:12] George L. Kelling: First of all, it comes through normal recruit training. That is that you begin to train officers to think about their decisions. By the way, I’m pleased to hear that quote. Forgive me but I think I said that very well. I didn’t [crosstalk]–

[00:08:27] Patrick O’Keefe: [laughs] Yes. You did.

[00:08:28] George L. Kelling: It seems to me that part of it is just a lot of on the ground experience by police officers and that is to learn to think about their decisions. Because it’s easy to say what you can’t do, but it’s very hard to say what you cannot do. Trying to figure out when one prohibits behavior, what level of intervention one takes; that’s one of the problems that I’ve seen with the application of broken windows.

In many communities, when it’s implemented, discretion is not emphasized enough in terms of the decision of the officer, and arrest is considered the best outcome of order maintenance encounters. That’s been a far cry from my position or Jim’s position, or I think the article as well. What we were saying in the article and this follows up by a 1989 article that Jim and I did in The Atlantic is: broken windows is a problem-solving mechanism.

Also, other agencies ought to be involved in the decision making in terms of how to handle the problems. One of the difficulties is, suddenly, one day, one says to the police, “You’re responsible for the mentally ill on your beat. You’re responsible for the homeless on your beat.” In some sense, that’s true, but it only means that they are to be bringing to the next other agencies which to a large extent have been failing their responsibilities in terms of meeting the needs of the mentally ill and the homeless.

It’s not just that the police officers, on occasion, might arrest — and I view arrests as a fairly radical solution to a problem, it’s that, one involves other agencies in terms of dealing with the problems that officers confront on the beat.

[00:10:16] Patrick O’Keefe: Another thing that Alex said, my moderator, who is a SWAT team commander, that I thought you’d appreciate was that, he said the worst thing that ever happened to policing was that they had air conditioners in their cars, [chuckles] because they didn’t have to get out and talk to people anymore.

[00:10:29] George L. Kelling: Well, I would heartily agree with that. It seems to me — and I think this is an important point, that as we moved policing into cars, we changed the very nature of American policing without realizing it. Up until then, police on the beat were there to prevent crime and they were preventive officers. Once we put police in cars, the mission changed from policing to law enforcement and that is responding after something happens.

Even police doing policing, doing foot patrol, doing other kinds of interactions with the community are, at times, going to do law enforcement, but law enforcement is something that police ought to be doing just on occasion rather than characterizing their entire role. Responding after the fact through 911, responding after the fact of an on view crime, that tactic failed.

What we’re trying to do now — and we call it community policing, but to move away from just mere law enforcement back to policing and that is the job of the police is to prevent crime in the first place.

[00:11:35] Patrick O’Keefe: It seems to me that what you’re talking about and what happens — it’s like when I get called when there’s a problem with an online community. The damage has already been done and now they want it fixed, but to get a sense of that problem, you have to become a part of that community a little bit and earn some of that trust to be able to actually effectively fix anything. You can’t just drop in and just enforce rules with a firm, hard hand and expect that the community will respond well.

[00:12:05] George L. Kelling: Well, you develop consensus. In broken windows, you recall one of the things that we talked about — I have to be careful because I don’t want to claim exclusive credit, and that is that you develop a consensus about what legitimate behavior is and you develop that with the street people as well. Maintaining order in the areas of Newark where I walked foot patrol, became easy because the standards were negotiated. The street people understood what the standards were. The potential miscreants understood what the limits were and had participated in that decision.

In terms of, “We’re going to do broken windows tomorrow,” kind of orientation, “We’re going to take police out of cars and tomorrow they’re going to do broken windows,” doesn’t take into account that whole negotiation process about what are the standards for this community. Again, this is a discretionary issue, it doesn’t matter what the neighborhood is, you’re going to have different standards of behavior that people are comfortable with. Some neighborhoods are very comfortable with high levels of disorder.

San Francisco is a city that has decided that it’s going to be comfortable with high levels of disorder. That’s very different than Milwaukee, for example, in which there are levels of order that wouldn’t be heard of in San Francisco. It depends upon the community. Even within a city, different neighborhoods are going to have different standards of behavior. Then, you negotiate with people to abide by that particular consensus. It seems to me it’s exactly parallel to what you’re talking about. You engage people in the process, even those people who might misbehave.

I can give you anecdotes. There’s this alcoholic guy who drinks a lot of wine, stands on the street in the back bay of Boston, calling out, yelling, behaving in a crazy way. Now this goes back some time, but when he goes into the liquor store to buy his wine, he keeps his mouth shut, he stands in line, pays for his liquor, goes outside and starts yelling and shouting and behaving in a quite mentally ill fashion. Again, he adjusted to the rules of the liquor store. He knew that if he was misbehaving in the liquor store, he wasn’t going to get any of his wine.

[00:14:08] Patrick O’Keefe: So he was capable of adjusting-

[00:14:09] George L. Kelling: That’s right.

[00:14:10] Patrick O’Keefe: – is what I take away from that. Capable to adjusting because he knows the rules and the standards have been laid out for him.

[00:14:15] George L. Kelling: That’s right.

[00:14:16] Patrick O’Keefe: Now, sometimes people talk about gentrification in relation to broken windows. I was curious, you mentioned different levels of disorder. San Francisco being different from Milwaukee being different from New York being different from Kitty Hawk, North Carolina where I live [chuckles]. Is there a line in there? Is it as simple as saying — I hate to point to graffiti because graffiti is not always a clear thing. Some people want this; some people don’t. Some property owners want it. Some see it as art; some don’t.

Is it as simple as saying like, “Okay, the community obviously responds well to this thing so this thing is therefore okay”? Or is it more nuanced than that in applying this theory of taking care of the small things so we don’t lead to bigger things while also not clamping down on what the neighborhood might simply view as culture?

[00:14:59] George L. Kelling: Well, I think one has to be very careful here because we tend to view community in terms of soft terms at the present time: community is good, neighborhoods are good, etcetera. Well, that’s not all the case. Communities and neighborhoods can be narrow-minded. One of the things that police have to do is to maintain the ability to say no.

There are a lot of communities who would be much happier with their police if the police would keep, say, African-Americans out of a predominantly white neighborhood.

Well, police have to learn to say no to that. That’s counter to democratic values and ought to be counter to police values. It is nuances, as you say. It has to be negotiated very carefully because there are people who would want to use the law to repress citizens who are engaged in lawful behavior. Now, the police can encourage people to not behave in ways that bother people, but at the same time, we have to be very careful that we say no when the demands are unconstitutional or illegal.

I recall a situation in which I was riding in the New York City subway and a very smelly person walked into the subway car. A woman came up to the officer and asked the officer to get the man to leave. The officer had explained to the woman, “I’m sorry, smelling bad is not an offense. He’s perfectly welcome here and there’s nothing that I can do or should do except protect his right to be here.” The woman wasn’t happy but that was a skilled officer who understood stuff.

[00:16:22] Patrick O’Keefe: Yes, I can see that, definitely. It reminds me of a conversation I had with those two law enforcement officers who work in my community. They said something along the lines of, “We don’t make the rules, the officer on the ground. We don’t make the rules, we just enforce them and have our discretion,” Where it sounds like in such a case this, we’re talking about like, okay, officers need to be able to say no, but if you have a problem with that, then you have to take it up the chain, right? Vote for a new mayor, vote for a new official, take it up the chain of elected officers and higher people if you want to effect that sort of change.

[00:16:52] George L. Kelling: Also, even when behavior isn’t illegal but it’s bothersome in the community, it seems to me an officer can play a mediating role and say, “Hey, come on. Knock it off. You know that you’re annoying these people. That’s not necessary.” Part of it is, what we lost touch with is the ancient Anglo-Saxon tradition of persuading people to behave. From the very beginning, if you look at Sir Robert Peel’s principles, the whole idea was to persuade people to behave rather than necessarily confronting them or arresting them.

It seems to me that part of the loss of the way of American policing for a long period of time was the idea that American police developed a much more confrontational style. All that we’re trying to do is to move away from that confrontational style towards a persuasive style, and that is, “Hey, come on. You know that that’s bothersome and you shouldn’t be doing that.” At the same time, I can give you examples.

For example, of using a park on hot summer nights, being too noisy. The park was technically closed, citizens complained. The officer’s solution to the problem is to go and talk to the users and say, “Look, I know it’s late. I know it’s hot. This isn’t Somerville, Massachusetts, these are three-decker houses. You can stay here but keep it down. Keep it quiet.” They did and the officer struck an agreement.

Now, he understood that they use it during the summer, they didn’t have other places to go. If they went on a corner in front of a grocery store, they’d get chased and shagged away from there. The park was a place where they could be. If they were quiet and they weren’t drinking and they weren’t misbehaving, why not just let them stay where it’s cooler? It worked out, everyone’s happy. The user’s happy and the neighbors were happy.

[00:18:33] Patrick O’Keefe: In those cases, it benefits — the officers are happy, too. [laughs]. Everyone’s happy because they’re viewed as better in the community which potentially — and not only it’s better for them to their job and they’re safer, but also, if there comes a time when they need help or they want information or they have a question-

[00:18:49] George L. Kelling: That’s right.

[00:18:50] Patrick O’Keefe: – maybe those kids grow up trusting the police, as opposed to mistrusting them if it had been handled differently.

[00:18:55] George L. Kelling: Well, it was a repeating story that goes on that goes on in many cities. It was every night, call the police, shag the kids out of there. That got a hostile response from the kids. Finally, one of the officers on bicycle patrol just finally said, “Hey, let’s talk for a few minutes. You guys are loud. If you’re loud we’re going to get called up. Just be quiet. Have your conversation. We won’t bother you, just behave yourself.”

The rules were there and the laws were there, but at the same time the officer, given the circumstances of the warm weather, the lack of availability of any space for these kids, negotiated a deal. That deal worked for as long as I knew about it.

[00:19:32] Patrick O’Keefe: Persuading people to behave, I don’t know if I’ve heard that phrase before but I like it. [chuckles] I think it’s a great way to think about a lot of the work we do in community, I want to relate it to something you said in a Politico Magazine piece you wrote about two years ago almost to the day.

You mentioned that — and you touched on this before but, “broken windows was never intended to be a high-arrest program. Although it has been practiced as such in many cities, neither [James Q.] Wilson, [the co-creator of the theory], nor I ever conceived of it in those terms. Broken-windows policing is a highly discretionary set of activities that seeks the least intrusive means of solving a problem—whether that problem is street prostitution, drug dealing in a park, graffiti, abandoned buildings, or actions such as public drunkenness. … Arrest of an offender is supposed to be a last resort—not the first.”

In online communities, our version of arrest might be permanently banning someone from that community so they can no longer participate. That, for the most of us, is generally viewed as a last resort. We don’t want to have a long banned list of people that can’t come to the community because it means that we have less activity [chuckles] in the community itself.

We really do try to persuade people to behave. A substantial portion of my time is literally sending people a very nice, polite, respectful, kind message and just saying, “Hello, I noticed this post was made here and we generally don’t allow that sort of thing here, but in the future maybe this is the way that we could do this.” I’m really just persuading them to behave or really meet within community norms.

On one hand, broken windows is about not letting people get away with minor infractions, but on the other, it’s not a high-arrest program, you need discretion. The idea of persuading people to behave makes me think of leniency. How do you view the role of leniency in this conversation?

[00:21:08] George L. Kelling: Well, I view this as very particular: that is, if an officer gets to know a particular deed, know the area well, know the players, he or she is going to know the difference between the repeat offenders that keep creating difficulties. Ultimately, after persuasion fails, then you begin to develop confrontational tactics which could ultimately result in arrest. But for other’s first time, we think about traffic enforcement and we think about leniency.

Here’s one more example where all of us, we really like the police when they’re lenient. The best public relations technique to the police that they have developed is not to give a traffic citation when somebody is speeding. We all want the officer to be lenient to that particular time. Again, it seems to me, it always depends upon the context: how many repeat offenders, what was the audience, what was the weather condition, what was the location, what did it mean generally.

Police make their discretion decisions based upon variables that one can identify. That’s where this whole idea of when you arrest one person and not another. It’s the history in the context. If you have somebody who’s constantly a repeat offender, that person you keep giving one more chance, one more chance, one more chance, when you really know, maybe without being confronted, that person is going to accelerate his or her misbehavior to a point that winds up being much more serious.

One of the reports by the Vera Institute, it says, “Maybe two or three nights in a jail is better than 8 to 10 years in prison.” That is that there comes a point where you cut people short. Enough is enough you have to stop here. Leniency is a disservice to this person as well as a disservice to the community. On the other hand, when we’re talking about minor offenders, if we start giving citations or making arrests or giving traffic tickets, just for the purpose of statistics or if there tend to be quotas in police departments.

That, it seems to me, gets away from the idea of broken windows almost totally because it takes away the idea of discretion and you’re arresting or taking other actions, not because you think it’s the best thing to do but that’s considered to be a bureaucratic good. One has to be very careful with that.

[00:23:22] Patrick O’Keefe: It’s really interesting and it makes me think about — I know in my online communities and the communities that I consulted with and guided, we have a system of documentation. It’s different for different scale. It depends on the number of people you have to interact with, etcetera. A community with a million people has to handle these problems maybe differently than someone with a thousand or ten thousand.

In our case, we have a documentation for any member that we have to interact with in any way that basically mentions what they did, when they did it, and the action we took. At any time, I can pull that up, essentially a file, and look at the member and that’s how I make my decision as far as what the next step is. Most of the time it’s not to ban someone. My measuring stake, and it’s very discretionary — within our community, we have a standard and understanding.

It’s that, if someone is clearly trying, then I’m going to give them the chance to keep trying and to come back. But there are things that people do when they just don’t care anymore, or they don’t try, or they’re purposely doing this repetitive thing that we’ve asked them very nicely [chuckles] not to do. That’s the time where — maybe the metaphor is a couple of days in jail. The reality is we’re just what kicking them off our online community.

Those relationships are very deep for people though, that can have a really deep meaning like any other friendship or any other relationship, but there comes a time when that file indicates, along with your own knowledge or know how of the community, that it really is a waste of our time, because my moderators are volunteers. It can take hours to deal with a particular problem depending on how complex it is. It’s not worth that moderator time to continue to spend it on people who aren’t trying. But those that are — I want to invest that time. But yes, when they demonstrate they don’t care, it’s time to go.

[00:24:59] George L. Kelling: Just think if your accountability structure was such that you’re rewarded for the number of people that you kicked off.

[00:25:04] Patrick O’Keefe: Right [chuckles].

[00:25:04] George L. Kelling: In some respects, that’s happened in areas of policing. That is: arrest has become a sign of productivity. Well, maybe at times, it is. Maybe at other times, it means just the opposite; that a lot of inappropriate authority is being used.

[00:25:19] Patrick O’Keefe: That’s a different world. That’s the criminologist’s world that you know and I don’t know [chuckles]. The idea of that metric, is that something that’s on the way down or up? What replaces it? What’s the measurement for police success? Is there a measurement? Is there some sort of data point?

[00:25:37] George L. Kelling: You’ve just taken me into the most difficult area of policing-

[00:25:39] Patrick O’Keefe: [laughs]

[00:25:40] George L. Kelling: – and that is: the ultimate measure is I think the lack of crime and the support of the community. Those are the ultimate measures. Measuring those is very, very hard, very, very difficult. It’s just that when we enshrine arrest as a sign of an officer’s productivity; rather than “did the officers solve problems?” We haven’t found effective methods yet to get department wide measures of solving problems as against just law enforcement.

I don’t want to back away from law enforcement as a means of solving problems because at times you use it, but it seems to me there are myriad of other ways to solve problems. We ought to be measuring an officer’s — and we use the discretion to solve problems: working with other agencies, working with the community in a broader sense rather than just thinking that arrest. At the same time, you know that the good officers are going to have a certain number of arrest. It’s a very, very difficult thing to develop metrics that really get at what we want out of police officers.

[00:26:41] Patrick O’Keefe: That’s something community professionals can relate to, too because it’s a constant battle in our industry to measure the success because, at the end of the day, we often are just hosting conversations, interaction, connecting between people. How they take that, they take that offline, they take it to email, they take it private. We don’t necessarily know how to measure that. We try to bridge that gap by using the data we have.

There’s also things like Net Promoter Score which is essentially surveying customers on satisfaction. How satisfied is the community? How satisfied are these people? Would they recommend it? That’s an area where — I also sympathize on a less — I don’t want to conflate the two. Policing and law enforcement is a life threatening sacrifice that people make to protect these communities. We’re just online community people. It’s not the same but related in some ways.

[00:27:28] George L. Kelling: It doesn’t diminish it to draw analogies, however.

[00:27:31] Patrick O’Keefe: You touched on this a little bit and I want to go back to it. The role of people in the community. First, online communities are very different and distinct from one another. They have different guidelines, different societal norms, and in many cases, the members of that community do help to find them. In your original article in The Atlantic in 1982, you described how different neighborhoods had different rules and that the rules were defined and enforced and in collaboration with the regulars, as you just said before, in that particular neighborhood.

In that Politico article from two years ago, you mentioned how good broken windows policing seeks partners to address it: social workers, city code enforcers, business improvement district staff, teachers, medical personnel, clergy, and others. But I find that when people talk about broken windows, it often really centers on policing and enforcement. Do you feel like the role that members of the community should play and caring for their own community is often overlooked?

[00:28:20] George L. Kelling: Yes. I think it’s a very powerful issue. If in a democracy, we believe that people can govern themselves. We have to also believe that citizens can police themselves. How that expresses itself can vary greatly. The role of citizens in terms of monitoring their own behavior, behavior of their children, and the behavior of the spaces that are under their control, it seems to me, can’t be overemphasized. It’s terribly important.

We will never have enough police or enough formal social control to deal with all the potential problems if citizens weren’t monitoring their own behavior. Think about the New York City subways, for example. In the late 1980s, there were just over three million passengers. Ridership was declining and there were almost 4,000 police officers in the subway. It was a lawless environment, completely out of control. Now, there are almost twice that number of passengers and they’re down to about 2,500 police officers.

Crime hasn’t gone up. There’s a little uptick now that we have to watch, but again, the need for police declined as the rules and traditions of the subway became incorporated and the citizens adjusted to them. The goal is always to use police as little as possible to maintain social control. We have a classic example of that being done by the doubling of passengers and a substantial reduction in the number of police officers in the New York City subway.

[00:29:59] Patrick O’Keefe: Thinking about community and the role people in the community should have reminds me of a conversation I had recently where — I can have this, because I’m the community owner-operator to a member, it’s a conversation I have once in a while where a member who really is a veteran member, who’s made a lot of contributions, who’s respected in the community and they do something that is generally out of character for them.

They’re just so mean to someone, or they’re so nasty, or they’re so rude to someone over an extended period of time. There’s one conversation, they just go back and forth, over and over again, and it’s so nasty and that’s just not what our community is about in this case. I just had a conversation with them in private beyond the normal one is, ” You’re a veteran member here. New members look to you, they look to you and they say, this is how we should act here. You’re an example to them coming in. When you act in this way, you are setting the tone for them to also act that way.” I think that disappoints me, people ask like, “What’s the most stressful thing you deal with in this work? Is it trolls or nasty people, or people just dropping in to disrupt things? No, it’s not that, that stuff is fairly easy, what is most stressful is when someone that the community trusts, they’ve built up credibility, and they’ve done so well, all of a sudden acts in a way that is totally the opposite of what the community is about.

[00:31:11] George L. Kelling: It’s such an interesting question and I haven’t really thought about it so I must apologize. It certainly would raise an issue about somebody in the neighborhood who’s been a traditional neighborhood leader who suddenly decides on an issue to go in another direction. Let’s suppose, a neighborhood leader for community development who suddenly decides that minorities are not supposed to move into the community, it would seem to me that one would want to try and intervene to get that person, to persuade that person. I’m not sure that I’m being helpful in terms of drawing any kind of an analogy here.

[00:31:47] Patrick O’Keefe: No, you’re being helpful, here’s something else I want to talk about: the misapplication of social science and theories like broken windows because you said that you feel that the theory, well, has been largely misunderstood. I’d like to talk a little bit about the misapplication of the theory because — and this is an easy low hanging example: when you conceived the broken windows, things like zero tolerance and stop-and-frisk were not what you had mind?

[00:32:12] George L. Kelling: Absolutely, first of all, zero tolerance implies a zealotry that I think ought not to characterize policing, and also it denies it the discretion. It seems to me that the largest misrepresentation has been, somehow, the dominant group imposing order on minority groups, which is the last thing I had in mind. I developed my share of broken windows not by working in upper middle-class neighborhoods or wealthy neighborhoods, I developed it on the streets of Newark, New Jersey which in the late ’70s and early ’80s was a tough neighborhood.

Moreover, even today, I could take you to the 10 toughest neighborhoods in the United States, sit down with neighborhood groups and ask them what their five biggest problems are, at least three of those will be problems of disorder, more likely four. These people are demanding order and many of them are minority citizens, the idea that this is the imposition — they’re dying for assistance from the police to maintain order, they don’t like the police whooshing in and whooshing out and harassing people; that’s not what they’re asking for.

When they get good policing, they are enormously gratified by it. These neighborhoods need police. The idea of the de-policing neighborhoods by putting police back in cars, I think, will be a tragedy for these particular communities. The demand for order in minority communities is very high. Now, that’s not justification for some of the bad things we’ve seen police do, it doesn’t mean the police have not been abusive towards minority communities.

There’s a sad history there. We have to be aware of it and be alert to it, but that can’t shape how we deal with neighborhoods now because we don’t back away because of past sins. We have to acknowledge that we made mistakes, apologize for making mistakes, and get on with providing the protection that neighborhoods want and need, and at times, need them quite desperately.

[00:34:07] Patrick O’Keefe: There’s one more thing I’d like to ask you about and it relates to misapplication of social science in just in a more general sense. Similar to how broken windows theory has been misapplied in policing or law enforcement context and its primary context, there’s a real danger that we, as whoever we are: online community builders, marketers, general business people, people of other disciplines, can abuse academic research like yours, by either not fully understanding it, or how to apply it, or simply hearing what we want to hear to confirm our own beliefs.

I was curious at your perspective on how can we ward against that abuse and that misapplication, and instead approach academic papers on social science and even criminology in a way that allows us to glean useful ideas while not also extrapolating beyond the scope of the work?

[00:34:58] George L. Kelling: Well, I wish I had an easy answer to that because-

[00:35:00] Patrick O’Keefe: [laughs]

[00:35:01] George L. Kelling: – [chuckles] as much as any social science theory has been vilified, broken windows is right up there. It seems to me that here, one has to maintain a historical perspective. In the final analysis, I think, the literature will correct itself. I’ve always had that belief. The problem many times is there are people who are social scientists, who either aren’t familiar with broken windows or who are lying about it to make the claims that they are. I find that bothersome.

I can provide with many examples of that. The argument for a long time before the Black Lives Matter movement began to criticize broken windows, there were academics who criticized broken windows that said it didn’t really have an impact on crime when, as a matter of fact, the two best experiments, one in New Jersey City, one in a New Hampshire city, two cities, social science experiments found a correlation between dealing with serious crime and broken windows.

One of the comments that I’d put on Twitter was that, although interviewed twice by NPR, and I even sent them copies of the articles, they chose to ignore that, winding up to the conclusion that there wasn’t much evidence about broken windows having an impact on serious crime. The problem becomes not just academics, but journalists and writers who are pushing an ideological point of view as opposed to an empirical point of view.

In my mind, one just has to keep at it. I don’t attack my critics. I develop my own line of thought. I remain optimistic that over time, both the success in the field and the consistency of the idea, almost the universality of this simple idea of “small things matter,” will win out over the long haul. One just has to keep plugging away at it. That is the only answer that I can give to that.

[00:36:58] Patrick O’Keefe: Well, Dr. Kelling, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us today. I really appreciate it.

[00:37:02] George L. Kelling: I hope it was helpful.

[00:37:03] Patrick O’Keefe: It was.

[00:37:04] George L. Kelling: Thank you very much.

[00:37:06] Patrick O’Keefe: We have been talking with Dr. George L. Kelling, co-creator of the broken windows theory, senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, and emeritus professor at Rutgers University. Thank you to Bill Johnston, Derek Powazek, Gail Ann Williams, Sarah Hawk and Scott Moore for their input into this episode of the show. For the transcript from this episode plus highlights and links that we mentioned, please visit communitysignal.com. Community Signal is produced by Karn Broad. We’ll be back next week.

If you have any thoughts on this episode that you’d like to share, please leave me a comment, send me an email or a tweet. If you enjoy the show, we would be so grateful if you spread the word and supported Community Signal on Patreon.

Thank you for listening to Community Signal.

“If a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken.” So says the broken windows theory, introduced by George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson in 1982, and widely adopted in law enforcement circles.

“If a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken.” So says the broken windows theory, introduced by George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson in 1982, and widely adopted in law enforcement circles.